Lighting, Composition and Subject

Lighting Part 4: The Angle of Light: Phase Angle, Advanced

by Roger N. Clark

The direction and quality of the light on the subject are the

most important keys to image impact. The subtleties of phase

angle can make the difference in image impact. Apparent sharpness

(accutance) is also impacted by phase angle, as are color and shading.

This article describes positive versus negative phase angles and

the impact on imaging quality.

The Lighting, Composition and Subject Series:

All images, text and data on this site are copyrighted.

They may not be used except by written permission from Roger N. Clark.

All rights reserved.

If you find the information on this site useful,

please support Clarkvision and make a donation (link below).

Introduction

Understanding phase angle and its effects is key to understanding light,

the angle of light and image impact. See part 3 (above) for basics of

phase angle. This page describes more advanced aspects of phase angle.

Remember, phase angle is the angle between the light source (e.g. the sun)

and the viewer from the position of the subject. The photographer can

control the phase angle by choosing where to stand, in conjunction with

the time of day and/or day of year. I will show that low phase angles

(the sun directly behind you) produce lower impact images, and present

evidence for the best phase angles to produce images with form, texture,

and impact.

Direction of Light: low Phase Angles and the Loss of Shadows

Shadows are important in many aspects of photography. Without shadows,

an image only changes intensity by the reflectance/transmittance intensity and color.

Images will usually

appear flat, without form. With shadows, 3-dimensional objects show form.

But more importantly, shadows on the fine scale show texture in an image,

whether the shadows cast by grains of sand on a beach, shadows cast by

hair or fur, or shadows cast by bird's feathers.

Examine the images of the great blue heron in Figure 1a. The image on

the left in Figure 1a was made at a phase angle of about 10 degrees.

The sun was directly behind my back and the sun just over my head.

This is the "point your shadow at the subject" position popular with

some bird photographers. But there is no shading on the bird

and it looks flat. I moved to the left in the field for the image in

Figure 1a, right panel so that the phase angle increased to 30 degrees.

The sun was then over my right shoulder and the two images were obtained

within a few minutes of each other.

Examine the differences in the two images in Figure 1a. The 10-degree

phase angle image shows the bird as a flat two-dimensional object.

The leaves in the background are yellower with less color saturation than

the leaves in the 30-degrees phase angle image. The 30-degrees phase

angle image shows shading on the right side of the bird, giving it form.

But that is not all, look at the feathers on the bird's back.

The 30-degree phase angle image shows that the feathers cast small

shadows. That adds texture and the impression of sharpness.

Figure 1a. Image of the same bird made at 2 different phase

angles and within 3.5 minutes of each other. The 10-degree phase angle

image lacks shading, both at the macro as well as the micro level.

Macro shading gives form (the shading on the bird's neck and body

in the 30-degree phase angle image). Micro shading gives texture (the

small shadows cast by feathers in the 30-degree phase angle image).

See Figures 1b, 1c, and 1d for closer examples of micro shading.

An interesting effect is seen in images made at low phase angles.

As shadows disappear because the light source (e.g. the sun) is behind the

viewer, one sees little to no shadows. Besides macro shadows giving form,

the micro shadows disappear too. The micro shadows around fine detail

casts tiny shadows. It is those small shadows that are often responsible

for texture in an image. But more than texture, the shadows increase

contrast and contrast is in part a factor in the apparent sharpness of

an image. Indeed, it is the edge contrast that the popular "sharpening"

tool, unsharp mask, boosts. Unsharp mask boosts edge contrast, otherwise

known as accutance. Unsharp mask does not actually sharpen (see my

series on sharpening for more details).

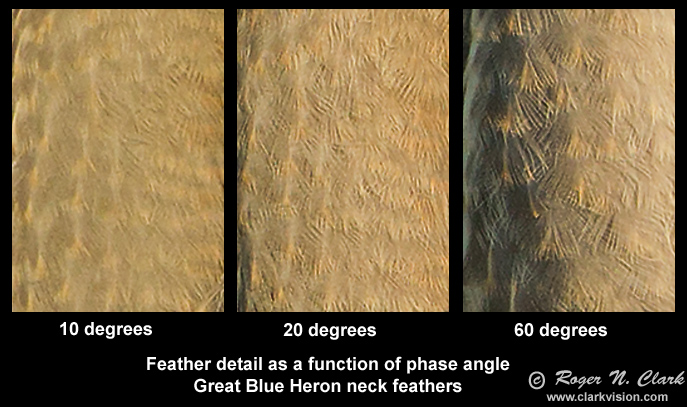

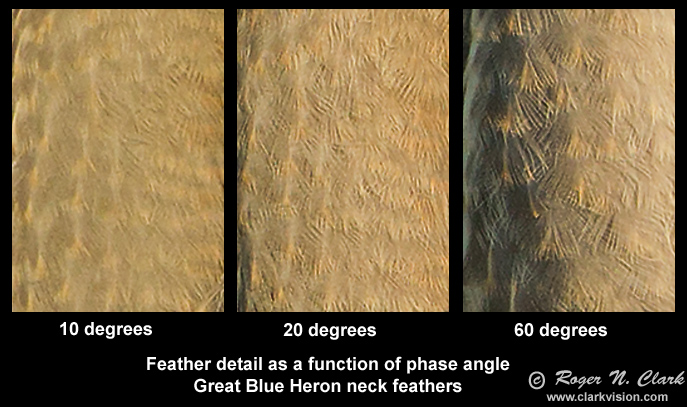

The images in Figures 1b, 1c, and 1d illustrate the micro shading changes

with phase angle. At phase angles of about 10 degrees and less, there is

little micro shading (as well as little in macro shading). Examine the

images in Figure 1b (the neck region of the bird in Figure 1a) and in

Figure 1b (the back of the bird in Figure 1a). The 10-degree phase

angle images lack fine shadows and appear less sharp. At 20 degrees

phase angle, the shading is large enough to give higher edge contrast

(accutance) and appears sharper. At 30 degrees phase the effect is

quite pronounced. All the images are in great focus.

There is an additional factor of low phase angles. As the shadows

disappear, and the fine edge contrast decreases, the contrast for

autofocus systems in your camera decreases and autofocus accuracy drops.

This can be a problem in fast action photography as the camera

has less time to achieve focus as contrast decreases as a subject moves

toward low phase angles.

Figure 1b. Enlargement of the neck region of

the bird in Figure 1a. At low phase angles ( less than about

10 degrees) insufficient shadows are cast by the feathers on a tiny

scale, so the image loses texture, accutance and apparent sharpness.

Figure 1c. Enlargement of the back area of

the bird in Figure 1a. At low phase angles ( less than about

10 degrees) insufficient shadows are cast by the feathers on a tiny

scale, so the image loses texture, accutance and apparent sharpness.

Note too the changes in color versus phase angle.

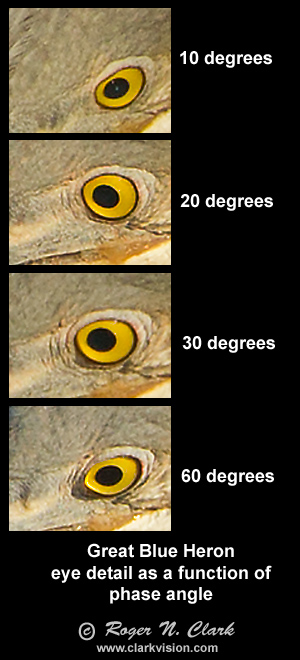

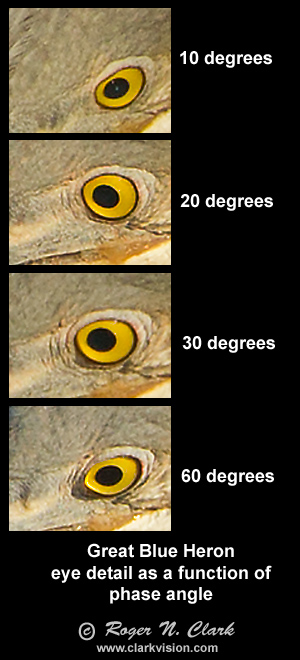

Figure 1d. Enlargement of the eye area of

the bird in Figure 1a. At low phase angles ( less than about

10 degrees) insufficient shadows are cast by the feathers on a tiny

scale, so the image loses texture, accutance and apparent sharpness.

Note too the changes in color versus phase angle.

The edge of the pupil of the eye appears equally sharp in

all images because there is high edge contrast, and that shows the images

are all focused well.

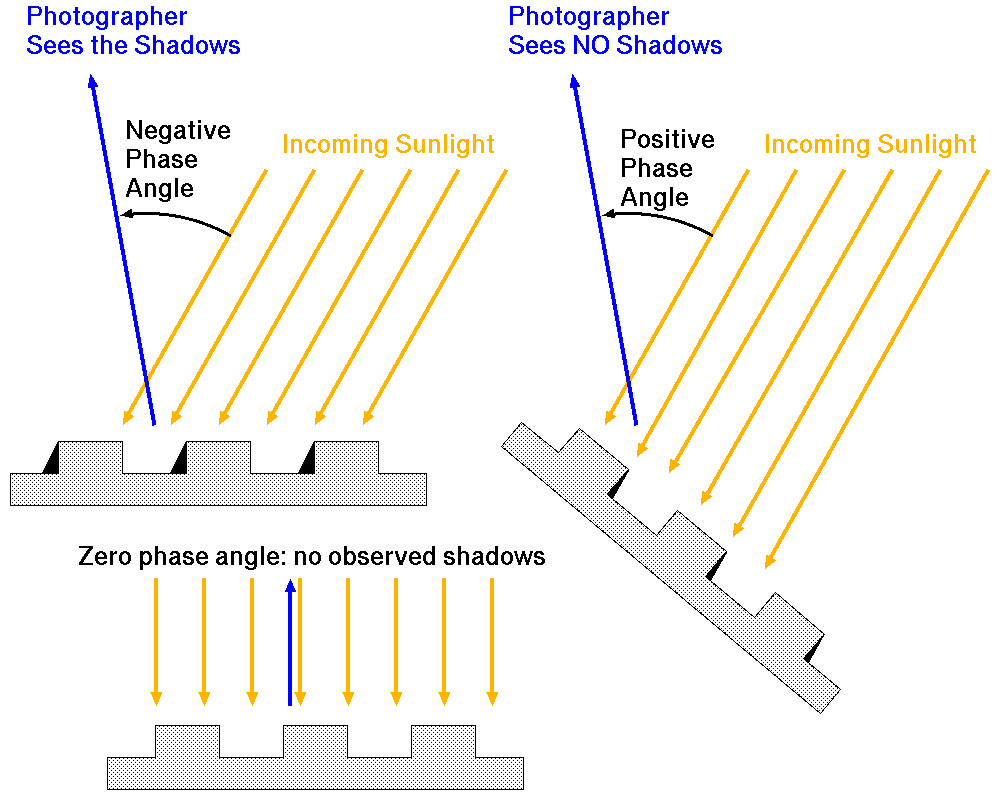

Positive versus Negative Phase Angle

Some may have already noticed that the micro shading on the bird in Figure 1

is not the same across the bird. This is because the bird is 3-dimensional,

and the angles of incident light and the viewer with respect to

the local area on the bird varied. For example, in Figure 1b, on the left side

of the bird's neck, the micro shadows are quite apparent while on the right side

of the neck, there are no shadows. This is because some of the phase

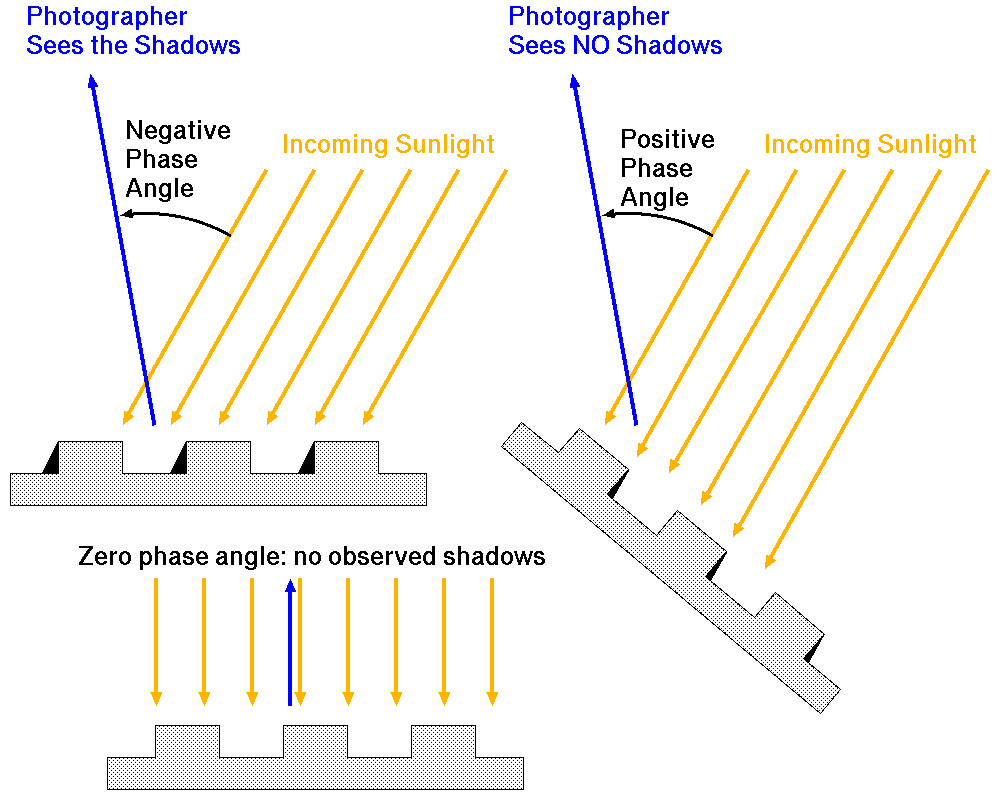

angles are negative, and some are positive. Figure 2 defines when the

angles are positive and when they are negative.

Figure 2. Phase angle can be positive or negative. Negative phase

angles are in the direction that emphasizes the shadows, positive

phase angles emphasize the lit side of the subject.

The Lunar phase angle sequence, presented in Part 3 of this series, and in Figure 3, below, illustrates

positive and negative phase angles. Look at the 90-degree phase angle

in Figure 3. If high phase angles show micro shadows, why do we only see

craters near the lunar terminator (the vertical boundary between lit

and unlit sides of the Moon)? The reason is that near the terminator we

are seeing negative phase angles because the angle of incidence to

the incoming sunlight is high (near 90 degrees at the terminator) and we are viewing

the shadow side of the mountains and crater rims.

Further from the terminator, the sun is high in the lunar sky (for an astronaut

on the lunar surface) and all sides of mountains and craters are lit by the

sun from our viewpoint, thus positive phase angles. Diagrams presented below will further explain

the geometry. At low phase angles (e.g. the 4 degree image of the full Moon in Figure 3),

even though the incident sunlight varies from grazing to overhead, no shadows

are seen anywhere.

Figure 3. Lunar phase angles. Phase angles of the Moon as viewed from Earth range from near zero (<2

degrees and the Moon is in the shadow of the Earth during a lunar eclipse) to near 180 degrees when a thin crescent

(exactly 180 degrees has the moon between the Earth and the Sun during a total solar eclipse). Low phase angles

have the light source (e.g. sun) behind your back as you photograph your subject. Phase angles approaching 180

degrees means you are photographing into the light source. Note the changing shadows revealing craters as you

move away from near zero phase angle. This same effect occurs with everything we observe and photograph.

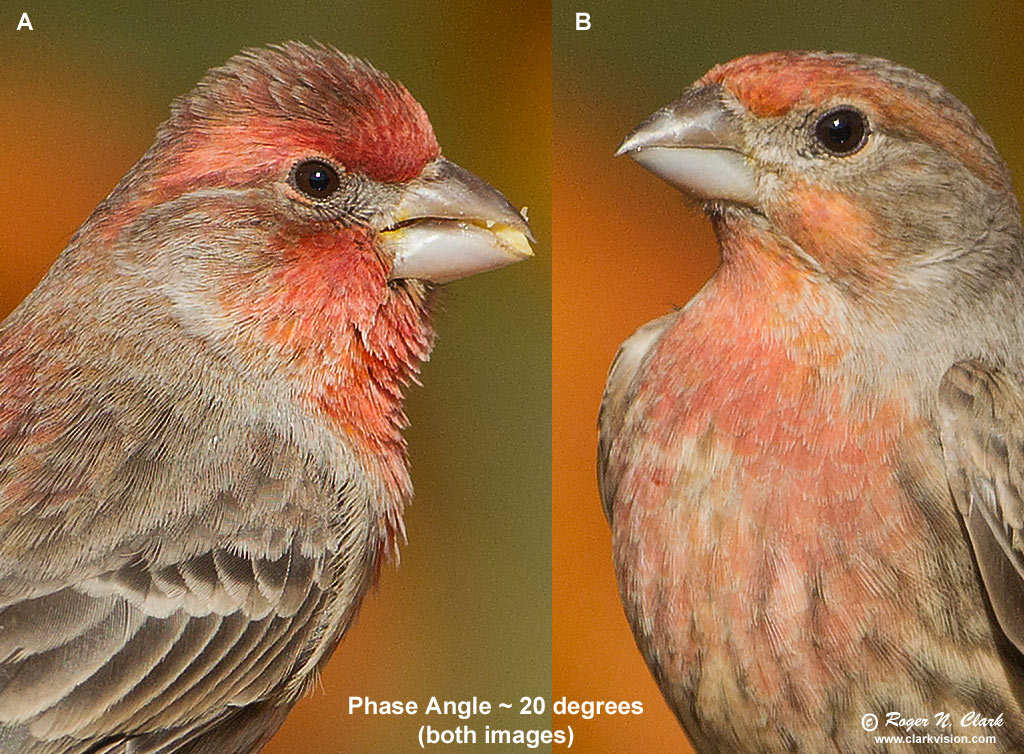

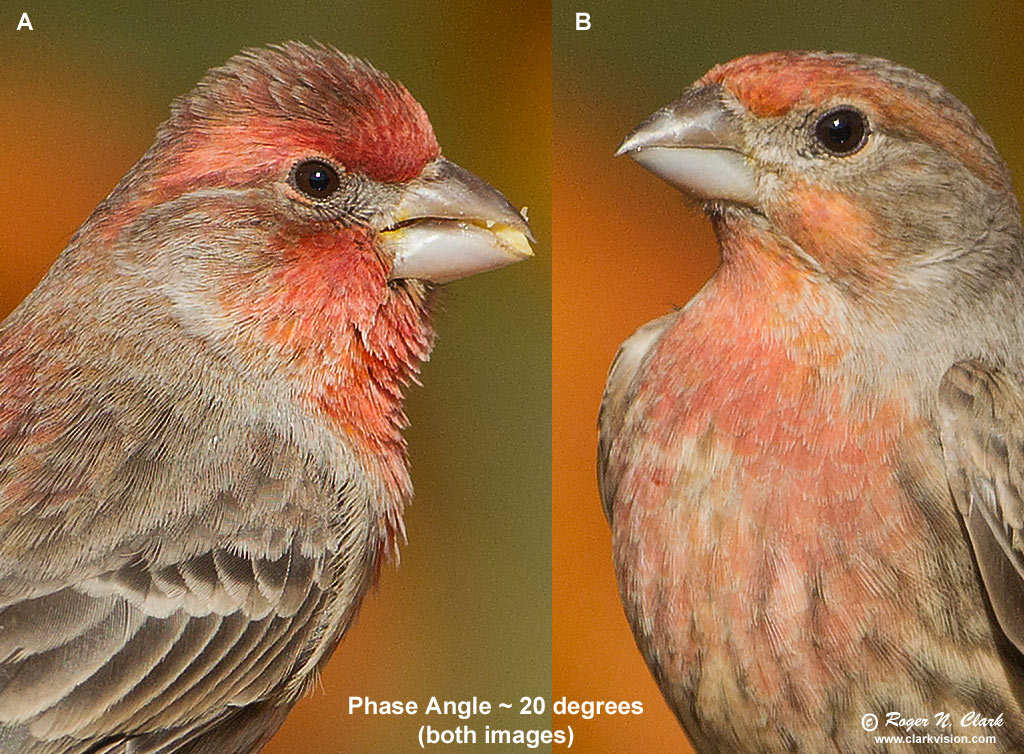

Now consider positive and negative phase angles on an animal subject,

like the finch in Figure 4. Both images were made from the same location

looking at the same spot at a phase angle of about 20 degrees. These are

two different birds, so ignore the change in color. Why are the effects

of micro shading so different? On the left, we are seeing predominantly

negative phase angles, and on the right we are seeing predominantly

positive phase angles. The sun was over my right shoulder.

Figure 4. Images of two finches, both made from the same location and

viewing the same perch where the birds landed. The sun is over my right shoulder

to give a phase angle of 20 degrees. Image A is predominantly negative phase angles

and image B is predominantly positive phase angles.

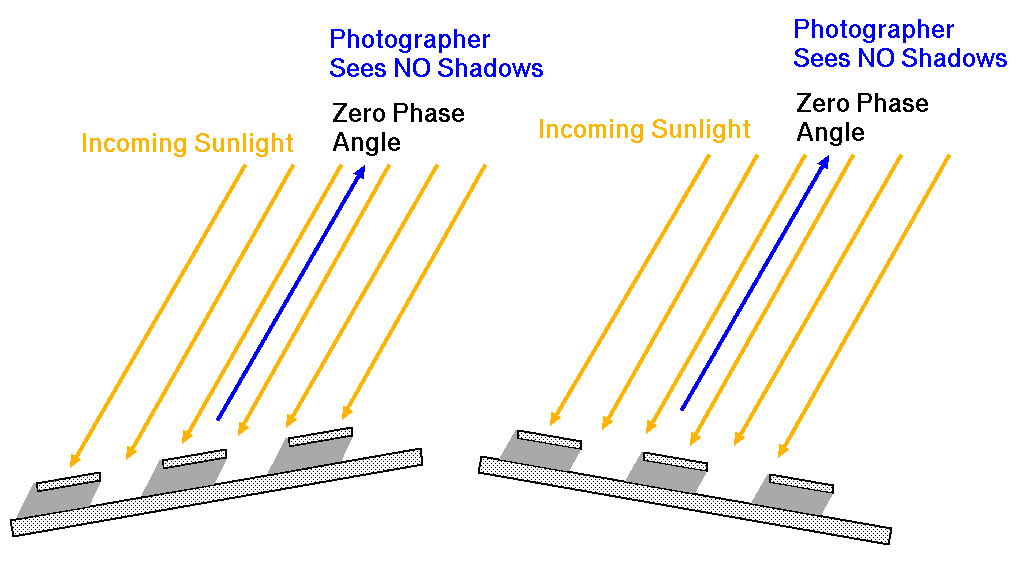

Figure 5. Illustration of positive and negative phase angles and

whether or not the viewer sees shadows. When phase angle approaches zero,

no shadows are seen by the viewer.

The diagrams in Figure 5 illustrate the geometric effects of positive and

negative phase angles. The orientation of the subject illustrated in Figure 5

is the same as the bird in Figure 4. In Figure 4a, the side of the bird has the sun

to the right casting small shadows for the camera to record, with similar orientation

as shown in Figure 5 in the negative phase angle panel. In Figure 4B the normal to the bird's

chest is pointing to the left. The sun is illuminating the same sides of the feathers

as seen by the camera and no shadows are seen. That is positive phase angle.

For a situation like that shown by the finches in Figure 4, I positioned myself

to have a pleasing phase angle (along with a good background). Then I waited

for the birds in their feeding activity to have the right position, like that in

Figure 4a to show the maximum texture in the feathers of the bird.

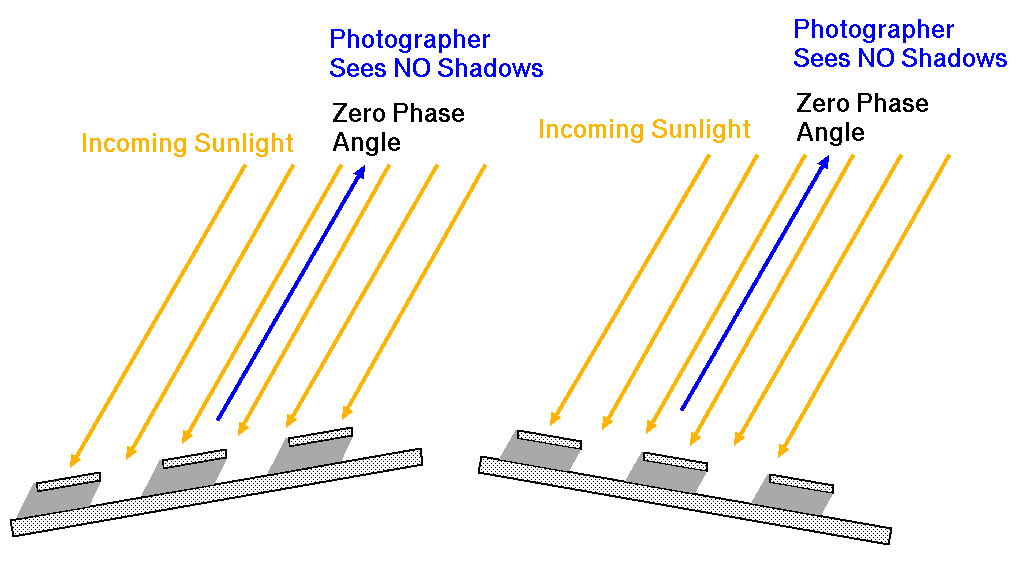

When phase angle is very low, no shadows are seen, regardless of the orientation

of the local surface. This is illustrated in Figure 6 and seen in practice with

the full Moon (Figure 3, left most image).

Figure 6. Illustration of low phase angle showing that regardless of the

orientation of the local surface, no shading is apparent to the viewer. The

image will appear flat with little to no fine texture.

Phase angle affects more than just the Moon and birds. Most surfaces show similar effects.

Look at the series of images of the Grand Tetons in Wyoming in Figures 7a, 7b, and 7c.

Wide angle scenic images can show large variations in brightness and shading as illustrated

in Figure 7a. The zero phase point at the lower right (bright area) in Figure 7a

seems out of place considering the rest of the scene. The mountains above center are

at a phase angle of about 30 degrees. Rugged mountains are often better represented

by higher phase angles, like those shown in Figures 7b and 7c.

Figure 7a. Mountain scene with a 28 mm lens on a 1.3x crop DSLR.

The zero phase point is at the lower edge, right of center where the bright

area is located (at the shadow sticking up below the bright area). The

tall mountain, the Grand Teton, is at a phase angle of about 30 degrees.

Figure 7b. Beautiful early morning light at a phase angle of about

70 degrees nicely shows the ruggedness of the mountains.

Note that the scene brightness is increasing toward the left, as phase

angles are decreasing from right to left. The zero phase point is to the left out of

the scene.

Figure 7c. Another beautiful early morning light at a phase angle of about

70 degrees nicely shows the ruggedness of the mountains. However, the

high phase angle has deep shadows in the center of the frame, losing

detail. One way to mitigate such deep shadows is if there were a few

clouds above the top edge of the frame reflecting light into the shadows.

As in Figure 7b, the scene brightness is increasing toward the left,

as phase angles are decreasing from right to left. The zero phase point

is to the left out of the scene.

Conclusions

Understanding phase angles along with the effects of micro and macro shading allows one

to position oneself in the field to record a subject in the best light. If you want

macro shading to show form and micro shading to show texture, then phase angles

greater than about 10 to 20 degrees are required. In other words, do not have the sun

directly behind you. Instead, put the sun over one shoulder, either to the right

or left.

If you want more contrast, then increase the phase angle to be side light. However,

contrast and dynamic range may increase too much for the camera to record in a

single exposure. Exposures must be more precise to keep the dynamic range

within the intensity range that the camera is capable of recording.

As the sun moves higher in the sky in the morning, the light becomes harsh (harsh light

will be explored in the following parts of this series). To minimize the harshness, then

one can point one's shadow at the subject. If the sun is 30 degrees high, for example,

then pointing your shadow at the subject means the sun is directly above your head and behind you,

and the phase angle is 30 degrees. The next chapter, Part 5, shows how to

determine the phase angle in the field.

If you find the information on this site useful,

please support Clarkvision and make a donation (link below).

The Lighting, Composition and Subject Series:

http://clarkvision.com/articles/lighting.part4

First Published May 5, 2009

Last updated November 1, 2014.